Global China

About

From a potential “responsible stakeholder” to a “strategic competitor,” the U.S. government’s assessment of China has changed dramatically in recent years. China has emerged as a truly global actor, impacting every region and every major issue area. From 2018-2020, the Brookings Global China project produced one of the largest open source diagnostic assessments of China’s actions in every major geographic and functional domain.

Brookings is now launching Phase 2 of the Global China Project which builds upon the research and analysis of the first phase, and shifts toward prescription, focusing on advancing recommendations on how the United States should respond to China’s actions that implicate key American interests and values. Through its unique convening power and deep bench of expertise, Brookings will convene a series of focused working groups to develop tailored recommendations on New Dynamics in the U.S.-China Relationship; Strategic Competition and Great Power Rivalry; Emergence of Critical Technologies; East Asian Security; China’s Influence in Key Regions Across the Globe; China’s Impact on Global Governance; Economics and Development; and Climate and Energy. These findings will help shape discourse on the tools available to the United States and its partners to address Chinese behaviors of concern.

Themes

U.S. POLICY RESPONSES TO CHINA’S GROWING ROLE IN THE WORLD

Technology

China’s recent advancements in AI and related technology have raised concerns in Washington and elsewhere. What are the policy implications for the United States’ overall economic competitiveness and its national security?

New dynamics in US-China relations

U.S.-China relationship is undergoing a transition toward intensifying rivalry even as it remains highly interdependent across a range of domains. How should the United States purposefully adapt its approach to China to best protect its fundamental interests?

Strategic issues

What approach can the U.S. pursue across strategic domains to integrate economic, military, and diplomatic measures to avoid conflict with China?

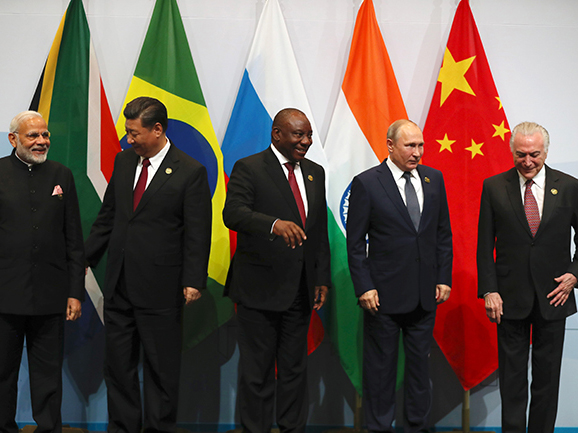

Great powers

What impact does great power dynamics have on U.S. efforts to manage the China challenge?

Indo-Pacific

How can the United States and China navigate intersecting interests in the Indo-Pacific?

Regional influence and strategy

What policy actions or strategy can – and should – the U.S. take to position itself as the partner of choice as China increases its activities in South Asia, the Middle East, and Africa?

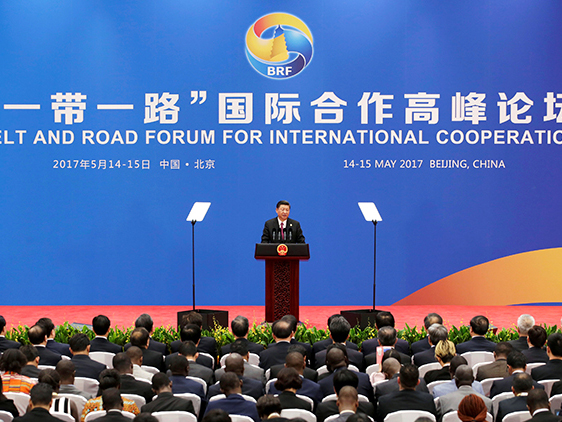

Global order and governance

China is increasingly using diplomatic and economic tools to challenge the terms of global order and governance; how should the United States and others respond?

Economics and development

What are the implications of China’s economic expansion and what can the U.S. and others do to set and promote global norms and standards?

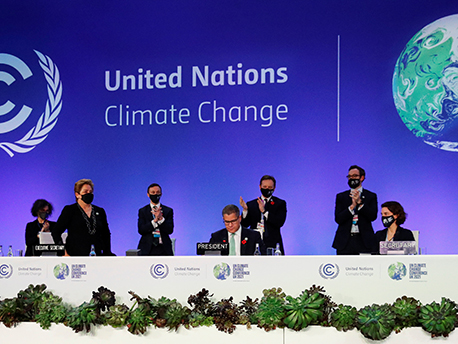

Climate and energy

Can the U.S. and China manage their relationship in a way that allows for collaboration on climate and energy challenges?

ASSESSING CHINA’S REGIONAL AND GLOBAL ACTIVITIES

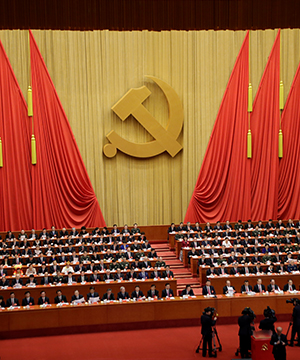

Domestic politics and foreign policy

How do President Xi Jinping’s personal ambitions and the centralization of power in the Chinese Communist Party affect China’s approach to foreign policy?

Domains of strategic competition

What are the implications of Chinese activity across various strategic domains — security, infrastructure, economic statecraft, and more — for the United States?

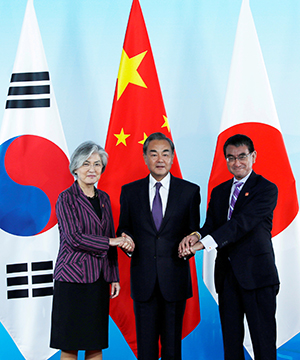

East Asia

How does China view its strategic requirements in East Asia as it expands its global influence and footprint?

Great powers

How is China navigating relations with other major powers?

Technology

China aspires to global technology leadership. Can it achieve its ambitions? What would the impacts be at home and abroad?

Regional influence and strategy

China now touches virtually every region in the world — how is China’s increasing involvement impacting South Asia, the Middle East, Latin America, and elsewhere?

Global governance and norms

From human rights to energy to trade and beyond, how is China approaching global norms and norm development?

Podcasts

Events

Contact

Foreign Policy Media

fpmedia@brookings.edu